Last year we released our second “Enabling Better Places” guide with our partners at the Congress for New Urbanism (CNU) and MEDC’s Redevelopment Ready Communities program (RRC). These two guides provide a strategy for communities of all sizes to examine their zoning and development codes, finding and removing common barriers to good development. This work grew out of our placemaking experiences with local communities finding that their own codes prevented them from achieving their goals.

The guides are available at https://www.cnu.org/michigan; some of the key lessons follow.

“More like this” and using what already works

The first guide, which we released in 2018, focuses on our beloved traditional main streets and the adjacent neighborhoods, and the ways that zoning codes often prohibit infill development that matches the existing pattern of the neighborhood. The newer guide looks at aging commercial corridors and shopping centers, and the potential to tame, evolve, and transform them into places that offer experiences more like those main streets and neighborhoods.

In each case, the code reform process is intended to help you reinforce, build on, and replicate the places that are already working well in your community, and to do so at the scale that’s already working. (There is an exception: some of our communities were built entirely in the automobile era and might not have a traditional main street to build on—but might want one. The suburban guide provides strategies for identifying appropriate corridors to begin evolving in that direction, but a full transformation will likely require a more large-scale planning and coding process.)

“Do the biggest little thing”

The code reform guides are specifically not intended for communities that are ready to undertake a full rewrite of their code. Instead, they strive to help you “do the biggest little thing,” to identify and implement those targeted changes in your code that will have the largest return on your effort—and to have confidence that a targeted, incremental approach can get a lot done. (Most codes will still likely benefit from that broader update, but you don’t have to wait until the stars align for that process to get things done!)

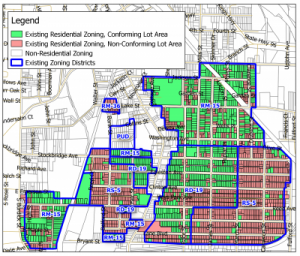

An analysis of Kalamazoo’s Edison neighborhood found 2/3 of residential parcels had non-conforming lot areas: a simple change to the dimension table removed a hurdle from hundreds of residents.

Some of the most critical code changes for better placemaking can be done with small text edits: requiring a functional entrance on the front of buildings, or prohibiting parking in the front yard setback. Many of the tactics can yield better places while also reducing administrative burden and easing requirements on developers: allowing shared parking across uses and counting on-street parking towards on-site parking requirements, enabling (but not requiring!) mixed uses in buildings, or simplifying permitted use tables to cover broad categories. (I once encountered a use table that included 14 different variations of arts, music, and photography studios, and that level of detail helps exactly no one.)

Removing code is as important as adding code

Often a software developer will find that the way to fix a problem or speed up performance in their programs is to delete bad code, or simplify overly complex code. The same is true for zoning: many of our codes have decades of edits layered atop one another, leading to confusion or conflicting requirements, and that overgrowth needs to be pruned back. The simplification of use tables mentioned earlier is a good place to look for this kind of streamlining.

In other cases, we’ve written codes for some “ideal” condition that local markets can’t support, and need to scale our code expectations to result in good, real development, rather than holding out for that someday-maybe perfect project. This is particularly the case for earlier waves of form-based codes—including some that I’ve personally worked on—which overshot their target with too many requirements.

Requiring multi-story development in weak markets is one common culprit: filling that gap in your main street with a really good single-story building is probably better than waiting decades for that unicorn developer to come along. Requiring mixed-uses in every building is another common issue that can make investments stall at the financing step, or result in ghost storefronts haunting the ground floor of a residential building. Yes, absolutely require retail frontages on your primary main street frontage, but also recognize that demand for retail square footage is limited, and consider allowing 100% residential buildings on other frontages in your downtown.

Know your tools, use the right ones

Code reform isn’t just about zoning, but about making sure you’re regulating things at the appropriate level and under a suitable code. If your zoning code covers an issue that’s already being addressed in the relevant building codes (like the minimum square footage of a studio apartment), health codes (cottage food production), or state of Michigan licensing processes (massage therapist qualifications), consider whether there’s really a need to also cover it in zoning, or whether you’re setting residents and businesses up for headaches as they try to navigate multiple regulations of the same issue.

Also consider whether your codes are being used as well as they could be to support your desired development outcomes. If a developer is working on the adaptive reuse of a building in your downtown, applying the Michigan Rehabilitation Code for Existing Buildings may be a better fit for the architecture they’ve inherited than trying to review their plans under the new-construction-oriented Building Code or Residential Code. If an infill project is proposed on an existing parking lot, you likely don’t need to require the on-site stormwater detention that greenfield construction would, removing that demand from the site. (You may still need the developer to provide stormwater quality improvements, even if no net impervious surface is added; review your MS4 permit for specifics.)

Make brands behave

National retailers and restaurant chains are known for standardized architecture and site plans, and their parking- or drivethrough-centric site plans can pose a challenge to local walkability and placemaking goals. Don’t allow these chains to undermine your work by defaulting to their suburban site plans—they have the ability to fit in to your desired context.

Many chain retailers also have “urban format” site plans that can fit into a traditional main street context or a corridor that’s evolving to be more walkable—but you’ll have to push them to bring those site plans, especially if you’re still in the early stages of evolving that corridor. Big box retailers like Meijer, Target, and Kroger will only locate urban format stores in larger downtowns, but smaller chain retailers, pharmacies, and restaurants do have the ability to fit in with your walkable neighborhood.

And—if they won’t? Keep in mind that their default parking-heavy site plan isn’t going to yield much per acre in property taxes or bring a substantial number of jobs, but it will sabotage your neighborhood’s sense of place for decades to come. Keep your community’s needs your first priority, and let that brand decide whether they’re going to work with you or walk away.

As one example of a national brand playing by local rules, Freeport Maine refused to waive their design requirements for McDonalds; the restaurant is located within a restored historic home. (Photo by Flickr user NNECAPA under a creative commons license.)

For more information:

- Download the Project for Code Reform guides at https://www.cnu.org/michigan

- Introduction to Code Reform video series: https://tinyurl.com/MichCodeReform

- For more information on applying this work in Michigan, contact Program Manager Richard Murphy at the League, [email protected], or City Planner Christina Anderson in Kalamazoo, [email protected], both faculty in CNU’s Project for Code Reform

- Development of the guides was supported by funding from MEDC’s RRC program; you may consult your regional RRC planner to discuss how these guides can support your community’s efforts to reach or maintain an RRC designation.

- Watch for sessions that include this content at the League’s upcoming Convention, September 22-24 in Grand Rapids and at the Planning Michigan fall conference in late October.